A Brief History of the Electric Vehicle

Both practical and polarizing, batteries have powered cars since the 1830s.

Capital One

Car buyers can now choose among dozens of electric vehicles (EVs), while plug-in hybrids and fuel-cell-powered electric machines add even more options for electron-driven transportation. Nearly all of the pure-electric cars and trucks you see on the road today were built during the past decade, but the ancestry of the modern EV goes way back, well before Nicolaus Otto patented the technology that led to the modern four-stroke internal-combustion engine and even before Carl Benz built the first true automobile. Let's take a look at the nearly two centuries of struggles and successes that led to EVs finally taking their place at center stage of the automotive world.

Prehistory

Electricity was poorly understood by scientists until the 1745 invention of the Leyden jar allowed the storage of a powerful electric charge. This device was a capacitor rather than a battery; the latter invention came to life thanks to Alessandro Volta in 1800. The need for steady, storable power by early telegraph companies led to the first reliable and predictable wet-cell batteries in the middle 1830s, and inventors began building impractical-yet-dangerous EVs in their sheds.

The U.S. Department of Energy gives credit to Robert Anderson for building the first quasi-useful carriage driven by a battery-powered electric motor in 1832. Genuine point-A-to-point-B EVs had to wait until two additional technologies arrived: practically rechargeable and reliable supplies of electricity. The batteries came with the lead-acid cell in 1859, and most large European and U.S. cities began getting usable electric power during the 1890s. That power was initially used mostly for lighting, which gradually pushed gas illumination aside.

Some Method, Lots of Madness

During the 1890s, the usual corps of gearheads vied with one another to find a way to make a buck designing and building self-powered vehicles based on carriage, bicycle, and locomotive components. For motive power back then, you could go with one of three options. One was external combustion, such as a steam engine with a boiler that took forever to heat up and tended to explode with often-apocalyptic results. Another choice was internal combustion, most often with a giant flywheel and difficult-to-control throttle, burning fuels ranging from coal dust to gasoline of varying quality. The third choice, electric power, came with somewhat safe lead-acid batteries and much quieter electric motors (though with the same scary suspension, steering, and brake hardware as the combustion-fueled heaps).

The First True EVs

Many car pioneers experimented with at least a couple — and sometimes all three — of these power types before settling on a favorite. Even such soon-to-be-famous names as Ransom Olds and Henry Ford wrenched on electric-powered buggies. The first sort-of-mass-produced EV that an ordinary citizen could buy was the 1895 Electrobat. It was produced by Electric Carriage & Wagon, the earliest ancestor of Chrysler.

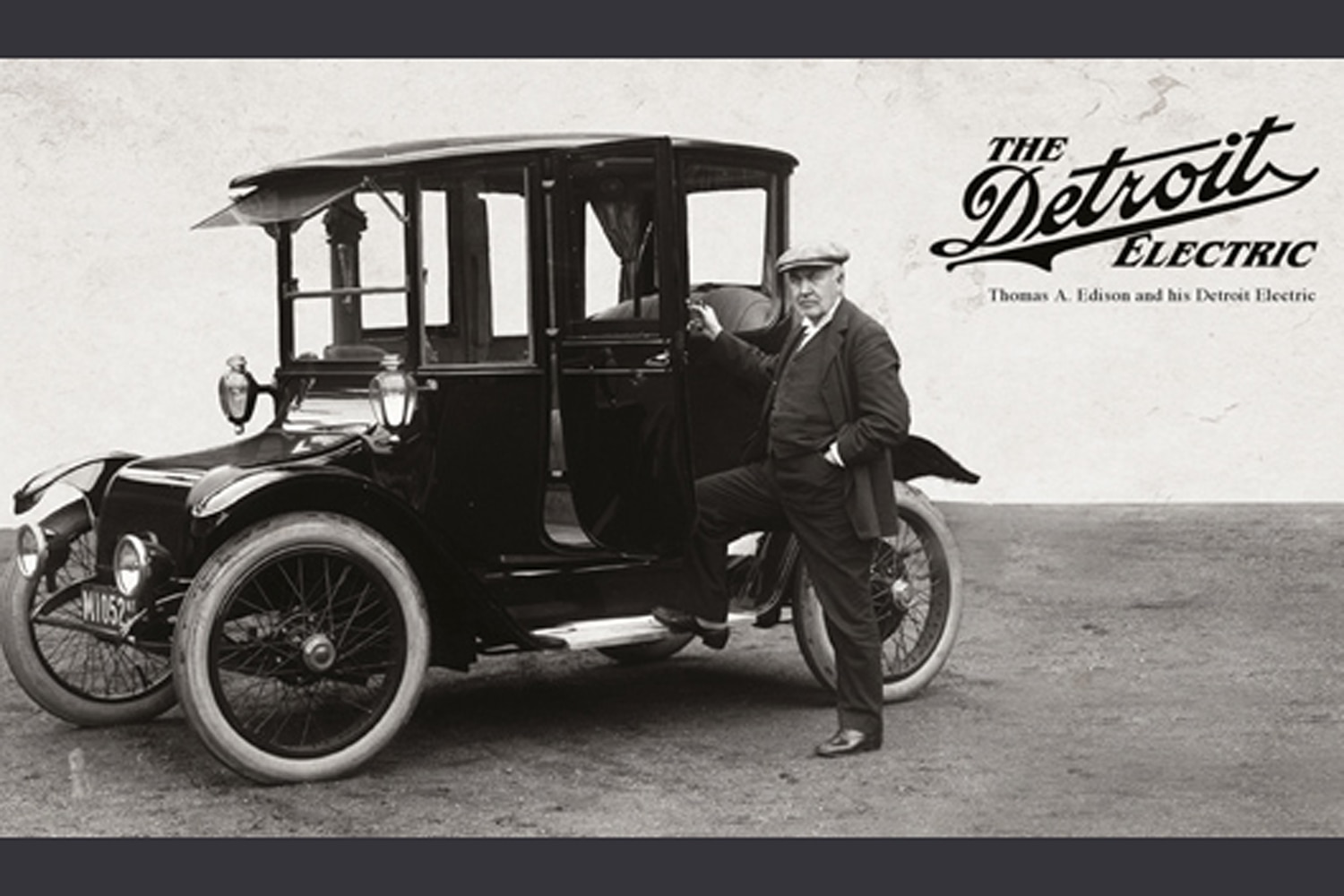

Large and small manufacturers of cars sprang up like weeds around the turn of the century. By 1900, more than a third of automobiles sold were powered by electricity. Studebaker's first foray into automobiles was the 1902 Electric, while the Fritchle Electric Automobile put Denver on the EV map in 1904, and the Detroit Electric sold well into the early 1920s. Technological advances eventually made the four-stroke gasoline engine safe and reliable, Henry Ford perfected the art of cheap manufacturing, and electric cars had to cling to an ever-narrowing niche for decades to come. The 1920s through 1960s had some interesting EV developments, but nothing that could compete for the car-buying money of non-adventurous consumers.

Detroit Electric

Detroit Electric

EV Revival

When air pollution became a much-publicized problem in the 1960s, followed by repeated oil shocks beginning in 1973 and good-running EVs on the moon, inventors large and small returned to the EV in force. Hobbyists sought out junkyard batteries and surplus motors, while big car companies experimented with promising prototypes. In 1974, Sebring-Vanguard introduced the odd-looking Citicar, an EV that would hit nearly 50 mph and travel 40 miles on a single charge, and Jet Industries sold more than 1,400 electric-converted Subaru Sambars, Dodge 024s, and Ford Escorts. Meanwhile, hobbyists built increasingly functional street EVs, generally by converting old internal-combustion cars.

Getting Real

The sales success of portable electronic devices of the 1990s led to safe-yet-lightweight battery designs — first nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) and then lithium-ion — just as California decreed that car manufacturers sell at least some zero-emissions vehicles. General Motors developed the EV1 (later models of which had NiMH batteries) in 1996, but it was the Toyota Prius gasoline-electric hybrid that showed the world that electric batteries and motors could work in a real-world street car. Hitting Japanese showrooms in 1997, the Prius did everything a car should do, and millions of hybrid vehicles have been sold since the Prius emerged. Batteries and motors got better, and consumers came to accept hybrid cars.

Tesla

The founders of Tesla made their millions in the ferment of Northern California's tech industry, beginning just as the EV1 made headlines and nearby companies struck it rich selling chips and battery patents to the hybrid builders in the car industry. The company was incorporated in 2003, with Elon Musk buying in to become the biggest shareholder in 2004. By 2008, the Tesla Roadster (built with the chassis of the Lotus Elise) was in production, and its 200-mile range startled the automotive universe. In 2010, Tesla bought an auto manufacturing plant in Fremont. It began building the Model S sedan in 2012, and suddenly EVs were both long-ranged and quick.

Where We Are Now

As power and range increased, EVs started to perform more like their gas counterparts instead of novelties, and the rush to own an EV began. Mitsubishi began selling the i-MiEV in 2009, with the big-selling Nissan Leaf appearing the following year. Nearly every other major manufacturer makes an EV or plans to do so. The Tesla Model 3 is now the bestselling electric car in history, with more than 1 million units sold. It will be a while before internal combustion goes the way of external combustion in cars, but that day might be coming.

Written by humans.

Edited by humans.

Murilee Martin

Murilee MartinMurilee Martin is the pen name of Phil Greden, a Colorado-based writer who appreciates Broughams d'Elegance, kei cars, Warsaw Pact hoopties, and the Simca Esplanada.

Related articles

View more related articles